“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

James Baldwin

1 in 10 people require mental health support (Bruckner et al., 2011).

It is estimated that by 2030, depression will be the…

- third highest cause of disease burden in low income countries and

- second in middle income countries (Mathers & Loncar, 2006).

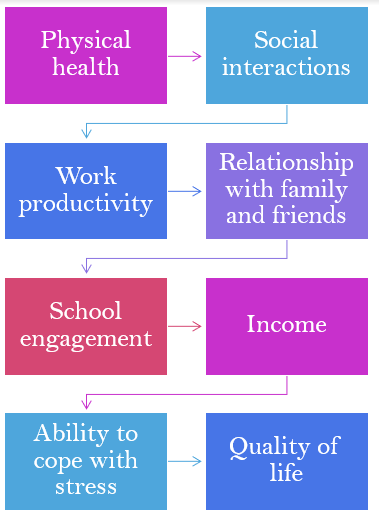

Impact of Mental ill-health

| Mental health issues also strain family, friends or carers, with a higher chance of | Mental health issues impact the economy through |

| – chronic stress – illness – reduced income | – straining the healthcare system – reduced work productivity and household income – impacted economic growth |

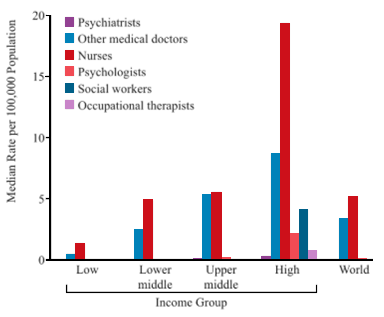

Investment in mental health services is often mis distributed between and across countries. High income countries spend up to 80 times more than low-income countries (Ritchie & Roser, 2018). However over 80% of people with mental disorders live in low- and middle-income countries (Rathod et al., 2017). To make matters worse, low-income countries may see as low as 2 health workers per 100,000 population (Bruckner et al., 2011). The graph below shows the graduation rates of professional mental health specialists between countries.

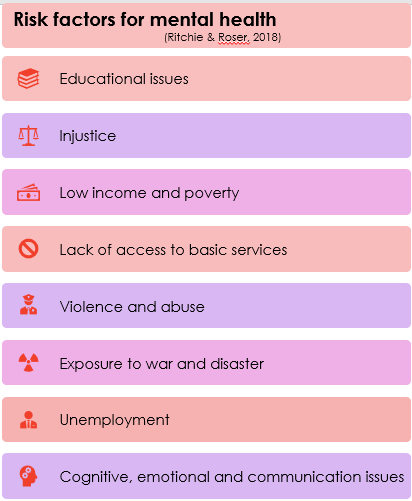

Children living in low-and middle-income countries are vulnerable to mental health issues because of the adverse childhood experiences they are exposed to (Escueta, Whetten, Ostermann, & O’Donnell 2014).

Why intervene in early childhood?

Early childhood is a developmentally sensitive period. This makes it the most cost-effective period to intervene (Karoly, Kilburn, & Cannon, 2005). Interventions have long-term cognitive, emotional, social and behavioural benefits (Everson-Rose, Mendes de Leon, Bienias, Wilson & Evans, 2003). This blog discusses how to implement an effective early childhood mental health intervention in low-and middle-income countries.

The Thinking Healthy Programme

The Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP; World Health Organisation, 2008) was developed by WHO to assess and manage mental disorders. The Thinking Healthy Programme is an addition of the mhGAP for perinatal depression (World Health Organisation, 2008). The programme aims to improve mother and baby physical and psychological wellbeing in non-specialised health-care settings (World Health Organization, 2015).

Practicality in low-and middle-income countries

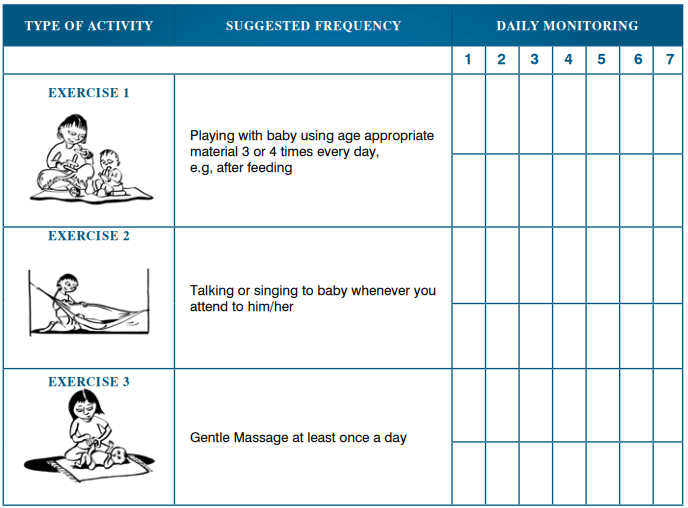

The Thinking Healthy Programme is a cost-effective programme, developed for use in low-and middle-income countries (Fuhr et al., 2019). The activities do not require background knowledge or materials and thus efficacy is not compromised in low-income countries. The types of activities include playing, talking and singing with baby, and using safe and appropriate household objects to promote child development.

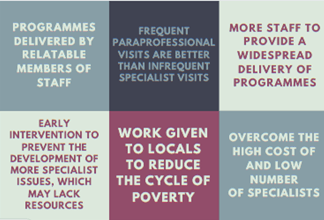

This programme does not rely on specialists, employing local paraprofessionals. This has many advantages including…

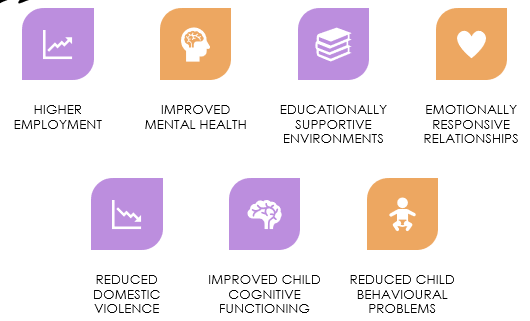

Paraprofessional home visits produce many positive outcomes for the family, including…

The emphasis on making the programme attainable and feasible in low-and middle-income countries is crucial. However, the effectiveness of the intervention is equally important as the programme needs to have an impact. This blog evaluates the efficacy of the Thinking Healthy Programme using Baker-Henningham’s paper (2013). This paper identified three factors of successful early childhood mental health interventions in low-and middle-income countries:

- activities designed to increase child development

- training caregivers to establish stimulative and supportive environments

- improving parental mental health

The Thinking Healthy Programme includes activities designed to enhance child development, establish stimulative environments and improve parental mental health. Activities include singing, playing and using safe household objects. Activities are cognitively stimulating and promote mental health through improving development and social interaction (Milteer, Ginsburg, & Mulligan, 2012). Children develop emotional-regulation and use resources and social systems to cope with risk factors for mental health issues (Engle et al., 2011).

Effective early childhood interventions focus on parental wellbeing and interaction with children (Baker-Henningham, 2013 ; Smith, 2004). Parental mental health issues may impact children genetically or environmentally through abuse, neglect and poor attachments (Smith, 2004). Child cognitive, emotional, social and behavioural development suffers when their parents have mental illness (Smith, 2004). The Thinking Healthy Programme facilitates parent-child interaction and improves mental health through supportive, nurturing, loving environments (Hamadani, Huda, Khatun, & Grantham-McGregor, 2006).

Implementation

Home visitors show mothers how to play with baby safely, effectively and in a way which promotes child development. Throughout the process, Thinking Healthy home visitors will praise parents and children to establish emotionally supportive and encouraging environments (Klasen & Crombag, 2013). An activity which may involve a household object may be a wooden spoon:

- Allowing the baby to play with the spoon to learn to interact with the world, and improve dexterity and motor skills

- Explaining the activity including the purpose, what the mother should do, and key language

- Demonstrating the activity to the mother using praise and key words. This may include

- hitting it against a pan to make a sound and saying ‘bang’

- saying the name of the object to enhance learning and language development

- pretending to mix something to enhance understanding of objects

- Asking mothers to do the activity, and supporting them, using key language and praise.

- Providing feedback and praise, reflecting on the activity. Discussing when this activity can be used.

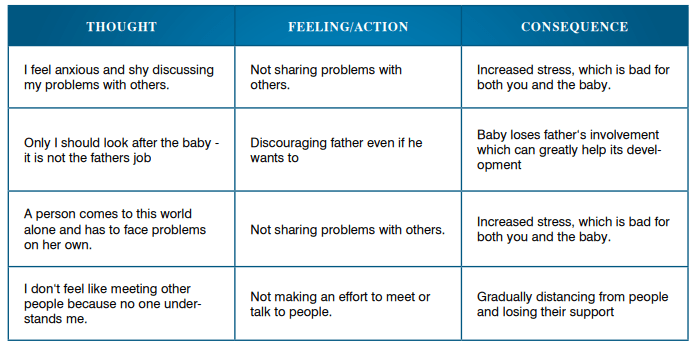

Activities benefit mother and child wellbeing, and establish a stimulative, interactive and engaging environment. This can promote mental health through quality interactions, stress-free play and enhanced resilience and ability to cope. The Thinking Healthy Programme also includes activities designed to directly improve parental mental health, to improve their ability to cope and engage with parenting (World Health Organisation, 2015). Cognitive behavioural techniques are used to challenge negative thought patterns (Grant, Townend, Mulhern, & Short, 2010).

Some problems with implementation (Britto et al., 2013).

- Rural areas and accessing families

- Training enough staff to meet the demand

- Getting materials to the low-to-middle income areas

- Financial and investment issues

Enablers to implementing early childhood mental health interventions in low- and middle-income countries (National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs, 2008; Worldbank, 2017;World Health Organisation, 2017).

- Assigning money to early childhood interventions as opposed to specialist mental hospitals, which targets fewer.

- Enhance government understanding that investment into early childhood education will have economic benefits

- higher income and employment

- reduced crime and substance addiction

- less pressure on healthcare

- reduce poverty

- enhance prosperity and human capital

- Employing local paraprofessionals to reduce the cycle of poverty and provide additional services.

- Getting support for early childhood interventions through financing, policy advice and partnership activities. Investments can see returns of $4 – $9 dollar return per $1 invested

Summary

The Thinking Healthy Programme is developed for low-and middle-income countries. It implements all of the core characteristics of an effective early childhood intervention as stated by Baker-Henningham (2013). The programme includes activities designed to increase child development such as playing with safe household objects. Caregivers are trained to establish stimulative and supportive environments through singing and playing with baby. It also works to improve parental mental health through CBT techniques of challenging negative thought patterns and engaging with their child (Grant, Townend, Mulhern, & Short, 2010). This early intervention of childhood mental health is crucial as the risk factors exposed to children in low-and middle-income countries are extensive. The impact of this exposure can be lifelong, and interventions later in life are less effective (Everson-Rose, Mendes de Leon, Bienias, Wilson & Evans, 2003). The Thinking Healthy Programme could be adapted to improve child and parent mental health across countries and contexts, and appears to be an efficient tool (World Health Organisation, 2015).

References

Baker-Henningham, H. (2014). The role of early childhood education programmes in the promotion of child and adolescent mental health in low-and middle-income countries. International journal of epidemiology, 43(2), 407-433. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyt226

Becker, A. E., & Kleinman, A. (2013). Mental health and the global agenda. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(1), 66-73. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1110827

Britto, P. R., Yoshikawa, H., Van Ravens, J., Ponguta, L. A., Oh, S. S., Dimaya, R., & Seder, R. C. (2014). Understanding governance of early childhood development and education systems and services in low-income countries. Office of Research Working Paper, UNICEF. Retrieved on 08/04/20. Retrieved from https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/iwp_2013_7.pdf.

Bruckner, T. A., Scheffler, R. M., Shen, G., Yoon, J., Chisholm, D., Morris, J., … & Saxena, S. (2011). The mental health workforce gap in low-and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89, 184-194. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.082784

Engle, P. L., Fernald, L. C., Alderman, H., Behrman, J., O’Gara, C., Yousafzai, A., … & Iltus, S. (2011). Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 378(9799), 1339-1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60889-1

Escueta, M., Whetten, K., Ostermann, J., & O’Donnell, K. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences, psychosocial well-being and cognitive development among orphans and abandoned children in five low income countries. BMC international health and human rights, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-14-6

Everson-Rose, S. A., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Bienias, J. L., Wilson, R. S., & Evans, D. A. (2003). Early life conditions and cognitive functioning in later life. American journal of epidemiology, 158(11), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg263

Fuhr, D. C., Weobong, B., Lazarus, A., Vanobberghen, F., Weiss, H. A., Singla, D. R., … & Joshi, A. (2019). Delivering the Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression through peers: an individually randomised controlled trial in India. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(2), 115-127. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30466-8.

Grant, A., Townend, M., Mulhern, R., & Short, N. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy in mental health care. Sage. Retrieved on 09/04/20. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CMl9fJHk03YC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=cognitive+behavioural+therapy+and+mental+health&ots=eXCIGyKQi7&sig=PjWVcOuNJNQTUOkYfIji3A-GYow#v=onepage&q=cognitive%20behavioural%20therapy%20and%20mental%20health&f=false

Hamadani, J. D., Huda, S. N., Khatun, F., & Grantham-McGregor, S. M. (2006). Psychosocial stimulation improves the development of undernourished children in rural Bangladesh. The Journal of nutrition, 136(10), 2645-2652. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.10.2645

Karoly, L. A., Kilburn, M. R., & Cannon, J. S. (2006). Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise. Rand Corporation. Retrieved on 18/03/20. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/RAND_RB9145.pdf

Kawakami, N., Abdulghani, E. A., Alonso, J., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., … & Ferry, F. (2012). Early-life mental disorders and adult household income in the World Mental Health Surveys. Biological psychiatry, 72(3), 228-237. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.009

Klasen, H., & Crombag, A. C. (2013). What works where? A systematic review of child and adolescent mental health interventions for low and middle income countries. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 48(4), 595-611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0566-x

Mathers, C. D., & Loncar, D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. Plos med, 3(11), e442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

Milteer, R. M., Ginsburg, K. R., & Mulligan, D. A. (2012). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond: Focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics, 129(1), e204-e213. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2953

National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs (2008). Workforce Development, Welfare Reform, and Child Well-Being: Working Paper No. 7. Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

Olds, D. L., Robinson, J., Pettitt, L., Luckey, D. W., Holmberg, J., Ng, R. K., … & Henderson, C. R. (2004). Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 114(6), 1560-1568. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0961

Rathod, S., Pinninti, N., Irfan, M., Gorczynski, P., Rathod, P., Gega, L., & Naeem, F. (2017). Mental health service provision in low-and middle-income countries. Health services insights, 10, 1178632917694350. doi: 10.1177/1178632917694350

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. Mental Health. 2018. Dostopno na: https://ourworldindata. org/mental–health (citirano: 15. 8. 2019). Retrieved on 16/03/20. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health.

Shah, A. J., Wadoo, O., & Latoo, J. (2010). Psychological distress in carers of people with mental disorders. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 3(3). Retrieved on 16/03/20. Retrieved from https://www.bjmp.org/content/psychological-distress-carers-people-mental-disorders.

Smith, M. (2004). Parental mental health: disruptions to parenting and outcomes for children. Child & Family Social Work, 9(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00312.x

World Bank. (2017). Early Childhood Development. World Development Index. Retrieved on 08/04/20. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/earlychildhooddevelopment#2

World Health Organization. (2008). mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Retrieved on 18/03/20. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43809/9789241596206_eng.pdf

World Health Organization. (2017). Mental health: massive scale-up of resources needed if global targets are to be met. Retrieved on 16/03/20. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/atlas_2017_web_note/en/.

World Health Organization. (2015). Thinking Healthy: A Manual for Psychosocial Management of Perinatal Depression (WHO generic field-trial version 1.0). Geneva, WHO. Retrieved on 09/04/20. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/WHO_MSD_MER_15.1_eng%20(1).pdf